Keller, D.; Ferneyhough, B. Analysis by Modeling: Xenakis’s ST/10-1 080262. Journal of New Music Research 2004, Vol. 33, No. 2, pp. 161–1711)

Abstract:

This paper proposes analysis by modeling as a complement to current analytical practices. We present an analysis of Xenakis’s algorithmic composition ST/10-1 080262. Two models were developed in order to study the temporal quantization processes and the streaming-fusion processes in this piece. Our study shows that fused granular textures could have been obtained by constraining the use of timbres to closely related classes and by increasing slightly the density of events.

Keywords: Analysis by modeling, algorithmic composition, stochastic music, Iannis Xenakis, quantification.

Commentaries:

This paper by Damian Keller and Bryan Ferneyhough is one significant example of the 2000's studies involving modeling and simulation for musical analysis. Here the authors suggest an approach for modeling and simulation as a complement for more traditional musicological methods. They do not pretend to propose an universal approach but actually they highlight that the own algorithmic nature of a piece as the ST/10-1 080262 by Iannis Xenakis, composed through a computer software implementing stochastic compositional principles, inspires, or rather demands a methodology which would consider the piece as "one among the many possible realizations of a particular compositional model." Thus, their goal is rather to "understand the model", a "pre-requisite to understand the piece", complementing what we may know about the composition by just investigating the final score or its recording.

Nevertheless, although the title makes clear reference to 'analysis by modeling', only the surprisingly short last two sections of the study show the application of their approach. Furthermore, one might ask how much of the chosen aspects of the piece helps us to 'understand the model' of the piece. Those chosen aspects were: "(1) the underlying quantization processes; (2) the process of fusion in dense textures."

Most of the article aims to deal with "inconsistencies among conceptual and technical procedures in stochastic music, and with the perceptual mechanisms brought into play by the sound processes found in ST/10."

When presenting Xenakis' piece, Keller and Ferneyhough make two observations which hardly could go unnoticed, showed in italic below:

(1) In the case of those pieces that require a "pre-compositional model in order to realize the work", the work being understood as "an instanciation of a general model", their observation should theoretically give the conditions to "infer the structure of the underlying model". We could interpret this assertion through the hypothesis that, as in the case of Xenakis ST pieces and Achorripsis, among others, some perceptually distinguishable elements were considered in first hand in the elaboration of the model - like glissando values being directly related to sections' event densities, instrumental timbres being distributed randomly and so forth -, Keller and Ferneyhough presume that, in ideal conditions, in a ideal listener, the underlying structure of the model which generated the piece could be perceptually appreciated. Otherwise, we could easily imagine practicable "pre-compositional models" which would be based in more abstract elements and parameters where there is no direct connections with perceptual elements in the resulting score, like with some extra-musical models integrated in a composer's own formalism and model.

(2) Accordingly, the authors state that "In practice, the direct realization of an algorithmic model as a musical piece is impossible". We could also interpret this assertion in the light of the first one. Keller and Ferneyhough might be saying that no composer is able to elaborate a model which could completely foresee how the listener will receive, appreciate the final piece. On that account, even with algorithmic electronic pieces, which would shorter the gap between realization and reception, the sound projection configuration (including room acoustics), required for the performance of such pieces, can never be precise, definite and this indetermination strongly influences what will be received by the listener.

The paper could have been a shortcut to know the specifications of the piece, but often we must to refer to the original text written by Xenakis himself in his "formalized music" book:

The Software ST

The piece is part of a group of related works. Xenakis used the software ST (named from Stochastic), coded not by himself but by François Génuys and Jacques Barraud 2) with the Fortran IV programming language, running on a IBM 7090 computer (capable of 500,000 elementary calculations per second). This software generated musical data in text format and afterwards Xenakis transcribed these data into traditional music notation, making inevitable compositional decisions, when adapting and approximating the precise data from the computer with respect to the constraints of musical notation.

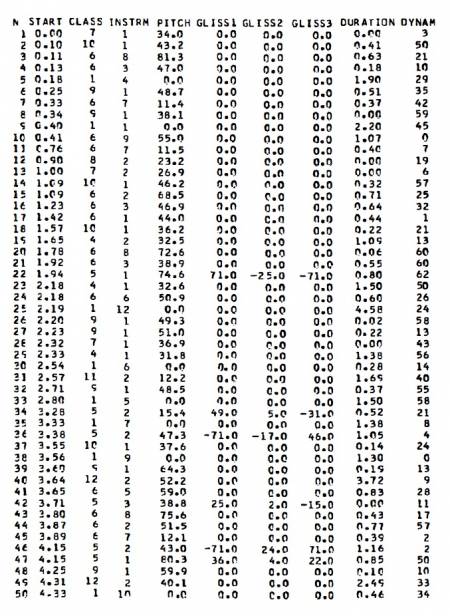

The output parameters produced by ST software were:

Attack Time (floating point number. e.g.: 0.00, 0.10)

Instrument Class (classes are based on timbre and instrument group, e.g: percussion, plucked, glissando, tremolo. Represent as integers.)

Instrument (violin, trumpet, flute, etc. Represented as integers.)

Pitch (floating poing number from 0 to 85)

Duration (in secs, floating point number)

Dynamics (represented by integers on a scale of 0–60)

Glissandi Speed ("three glissando values were produced either as a function of the section’s average density: (1) inversely proportional; (2) directly proportional; or (3) as a random distribution independent from the density. Only one of the three mappings was used per section. A positive value indicated a glissando toward a higher pitch and a negative value suggested a glissando toward a lower pitch." Represented as floating point numbers, meaning the number of semitones by one second, the value represented by the Pitch output being the initial pitch.)

The Piece

Some of the pieces composed with ST software follow a name convention, ST stands for stochastic, followed by the number of instrumental groups and then the number version of the piece and the date in which it was generated.

The duration of each section of ST/10-1 080262 is completely independent and was determined by a Gaussian distribution around a mean, say Keller and Ferneyhough, which in turn is an input parameter in the software. 3)

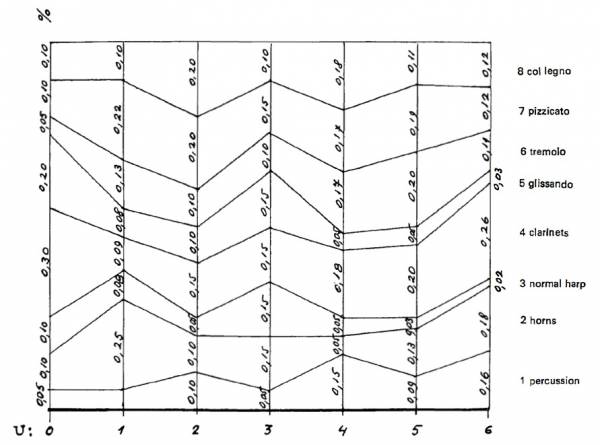

The density of each section, i.e. its "average number of events (note onsets)", was chosen at random upon a logarithmic curve with base e4). Keller and Ferneyhough remark that that choice of subsequent section densities was made through random deviations of the previous values, introducing a "short-term memory" in the process. The upper density limit on a given piece, says Xenakis, generally depends on questions of technical order (number of players, kind of instrument and technique) while the lower limit is arbitrary. He chose 0,11 sounds per second as a lower limit and 44,37 as the upper density limit for this piece. In other words, the density ranges from 0,11.e0 and 0,11.e6.

The instrumental choice of each section is stochastically distributed and related, respectively, with its density by the help of a "special diagram" (showed in the figure above), adds Xenakis.

Quotes:

- The conceptual separation between model and implementation of a musical piece has fostered the development of computer-assisted composition and sound synthesis.